In some parts of the world, record numbers of people are being diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In the United States, for example, government researchers last year reported that more than 11% of children had received an ADHD diagnosis at some point in their lives — a sharp increase from 2003, when around 8% of children had.

But now, top US health officials argue that diagnoses have spiralled out of control. In May, the Make America Healthy Again Commission — led by US health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr — said ADHD was part of a “crisis of overdiagnosis and overtreatment” and suggested that ADHD medications did not help children in the long term.

So what, exactly, is going on?

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

One thing that’s clear is that several factors — including improved detection and greater awareness of ADHD — are causing people with symptoms to receive a diagnosis and treatment, whereas they wouldn’t have years earlier. Clinicians say this is especially true for women and girls, whose pattern of symptoms was often missed in the past. Although some specialists are concerned about the risks of overdiagnosis, many are more worried that too many people go undiagnosed and untreated.

At the same time, the rise in awareness and diagnoses of ADHD has fuelled a public debate about how it should be viewed and how best to provide support, including when medication is required. The emergence of the neurodiversity movement is challenging the view of ADHD as a disorder that should be ‘treated’, and instead proposes that it’s a difference that should be better understood and supported — with more focus on adapting schools and workplaces, for instance.

“I do have a big problem with ‘disorder’,” says Jeff Karp, a biomedical engineer at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, who has ADHD. “It’s the school system that’s disordered. It’s not the kids.”

But many clinicians and people with ADHD argue that it is associated with difficulties — ranging from academic struggles to an increased chance of injuries and substance misuse — that justify its label as a medical condition, and say that medication is an important and effective part of therapy for many people.

“I hear a lot of people talking about ADHD being a gift and a superpower, and I do applaud that,” says Jeremy Didier, a clinician specializing in ADHD who is president of Children and Adults with Attention Deficit–Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD), a non-profit US group based in Lanham, Maryland, and who has ADHD herself. “But I do not want to downplay the impact that ADHD can have on someone’s life when it’s either undiagnosed or poorly managed.”

She and others say both models — neurodiversity and medical — have merit. “Bringing those two together in a meaningful and productive way, I think that’s maybe the biggest challenge” for the field, says Sven Bölte, a specialist in child and adolescent psychiatric science at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

A real rise

A slew of studies suggests that diagnoses of ADHD have gone up in many high-income countries in the past two to three decades — similar to a rise in autism diagnoses. The rate of new ADHD diagnoses in the United Kingdom, for example, doubled in boys and quadrupled in girls between 2000 and 2018, according to one study. In adults, the rate shot up even more. “We have numbers suggesting that we’re seeing a rise,” says Max Wiznitzer, a paediatric neurologist at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland, Ohio.

So what explains the surge? It doesn’t seem to be a big rise in the prevalence of the symptoms and traits that characterize ADHD — namely hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention, researchers say. When scientists use standard procedures to rigorously assess symptoms in representative samples of a population, they find that the ‘true’ prevalence of ADHD is fairly consistent in different parts of the world — estimated at around 5.4% in children and 2.6% in adults, according to two comprehensive global studies.

Experts say there are several reasons these figures are much lower than the 11% diagnosis level in US children that the country’s health authorities reported last year1. That number comes from the US National Survey of Children’s Health conducted in 2022, in which parents were asked whether a doctor or other health-care provider had ever said their child has ADHD. But this method of assessing prevalence would lead to inflated counts, says Luis Rohde, a psychiatrist and ADHD specialist at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Some children were probably misdiagnosed — perhaps by a physician without specialist training — and would not be classified as having ADHD in a thorough clinical evaluation. Some parents might have misremembered, perhaps if they were told that their child had symptoms without a formal diagnosis, he says. And some children who once had a diagnosis would no longer have received one at the time of the survey if their symptoms had waned and they were reassessed.

Researchers and specialists highlight other factors that are likely to be driving up the number of diagnoses. One is a change in diagnostic criteria in The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). In the fourth edition of this widely used manual, introduced in 1994, a child or adult ADHD diagnosis required the presence of at least six of a list of nine inattention symptoms and/or six or more of nine hyperactivity symptoms, and stipulated that these had to be present before the age of seven. (This reflects the idea that ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition that arises during childhood brain development.)

When the fifth edition, DSM-V, arrived in 2013, the criteria were slightly relaxed. Symptoms had to be present before age 12, and adult diagnosis required a minimum of five symptoms. (Children still had to have at least six.) “So when we expand the criteria, obviously you increase a little bit the prevalence,” says Rohde, who was involved in those revisions. It has also become more common for clinicians to diagnose ADHD along with other conditions, when in the past they tended to focus on one, says Bölte: “That fuels the figures.” ADHD commonly occurs with autism, as well as with anxiety, depression and other disorders.

The impairment requirement

Today, a thorough ADHD assessment involves collecting a detailed history and completing behaviour questionnaires, including input from family members and, for children, from schools. In the United States, the condition can be diagnosed by a range of health professionals, including psychiatrists, other mental-health specialists and primary-care physicians such as paediatricians, who might not have dedicated training in ADHD. But countries differ: in Brazil and many other low- and middle-income nations, people with ADHD symptoms tend to be sent to neurologists and psychiatrists for ADHD assessment and diagnoses, and there is a shortage of such specialists, Rohde says.

The DSM-V defines three ‘presentations’ of ADHD. People with ‘predominantly inattentive’ ADHD show symptoms such as making careless mistakes, struggling to sustain attention, losing things and being easily distracted. Those with predominantly hyperactive-impulsive ADHD have traits such as fidgeting, restlessness, talking excessively and interrupting others. In a third, combined presentation, people show both sets of symptoms. A diagnosis requires that symptoms are present for at least six months and in two or more settings (such as school, home, work); are not explained by another condition such as anxiety; and cause an impairment, such as struggling with schoolwork, losing a job or having relationship problems.

The impairment requirement is key, clinicians say. These traits vary across the population: some individuals are very hyperactive or inattentive, and some not at all. But people tend to be diagnosed with ADHD when their symptoms significantly interfere with their lives. “The medical part of ADHD comes in when your life is becoming derailed,” says Margaret Sibley, a specialist in psychiatry and behavioural sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

Bölte says that clinicians are interpreting the diagnostic criteria “far more liberally and openly” than in the past. This is another factor — aside from changes in the diagnostic criteria — that is driving the apparent surge in ADHD.

But working out when someone crosses the impairment line involves a subjective and sometimes tricky judgement, say specialists. And there is an ongoing debate about whether a person’s level of impairment should be defined relative to their own potential or to a population average.

What’s clear is that more parents as well as children are deemed as crossing that threshold. Wiznitzer says that when he diagnoses a child, “almost invariably [one of] the parents has it”, too. (That’s because genes are a major contributor to ADHD: the disorder has a heritability of roughly 70–80%.) Even though the parents were probably symptomatic as children, many were not identified as having the condition, he says. But now, they are.

ADHD on TikTok

Another reason why diagnoses have surged is an increase in public awareness of ADHD — fuelled by an explosion of discussion on TikTok and other social media.

Information online “connects with some people who have had these symptoms and impairments for a long time, but never understood what they were,” says Sibley. That leads them to seek information and professional help, pushing diagnoses up. And people might be eager to receive a diagnosis if it allows them to access help and services for themselves or a child, such as adaptations to support learning at school.

The surge in ADHD has led to concerns, particularly in the United States, about questionable diagnoses being given without a thorough clinical evaluation — through online services, for example, or by medical professionals without ADHD training. “They’ve got a visit for 15 or 20 minutes, and the diagnosis is made,” says Stephen Hinshaw, a specialist in child and adolescent mental health and ADHD at the University of California, Berkeley. But Didier says that a bigger problem is the number of people with ADHD who are undiagnosed or untreated. She emphasizes how important it is for people to have access to a thorough, accurate assessment from a trained professional who specializes in ADHD.

The lack of recognition of ADHD is a particular problem in low- and middle-income countries, says Rohde. “The problem here is clearly underdiagnosis, stigma and undertreatment,” he says, which particularly affects “vulnerable people and communities.”

Many specialists say they’re observing a rapid rise of diagnoses in girls and women. In part, that’s thought to be because women and girls are more likely to have symptoms of inattention — rather than more-noticeable hyperactivity — and to find organizational and other strategies that ‘mask’ those symptoms. Didier says that, despite being an ADHD specialist and diagnosing the condition in three of her sons, she and other ADHD practitioners missed the signs and symptoms in her daughter until she was a teenager. “It’s egregious that we don’t have more research on ADHD trajectories in women,” Sibley says.

Changes in the world itself are yet another possible contributor to increased diagnoses. Some researchers speculate that schools, work, technology and other aspects of modern lives have become so complex and taxing that they are pushing more people beyond the threshold of impairment. In Sweden, says Bölte, schools are sometimes chaotic, with complex schedules and grading systems. “Many students are very confused and fed up with school and do not understand it any more,” he says.

A study published last year revealed that parents think their children are struggling more. The research team examined how parents viewed the ADHD symptoms of more than 27,000 nine-year-old children born in Sweden. Parents consulted in 2016–18 tended to say that their children were more impaired than did parents consulted in 2004–06, even though their kids had the same number of symptoms. “Environment around the child is crucial,” says Samuele Cortese, who studies ADHD at the University of Southampton, UK, and was involved in the work.

Context is key

Karp describes ADHD as “context-dependent”. In a school where children are expected to sit still and be quiet, “it makes these traits seem like a problem”, he says. But when someone with ADHD is in an environment that nurtures and empowers them, they “can then channel their neurotype to do incredible things.” Karp is not against medication — and sometimes takes it himself — but would like more emphasis on institutions and society evolving so that people with ADHD can thrive.

Researchers, meanwhile, are finding evidence that the severity of symptoms can vary over time. In a 2021 study, Sibley and her colleagues analysed detailed records of more than 550 children who were diagnosed with ADHD and followed for up to 16 years. The researchers found that 64% of young people had fluctuations in ADHD — times when their symptoms faded but then recurred.

Sibley and her team hypothesized that people’s symptoms might flare up when they were facing increased demands in their lives, such as when starting a new school or having a child. But in fact, the opposite seemed to be true, according to a later analysis by Sibley and her colleagues. This could be because people are able to take on more responsibility when their symptoms abate. But the alternative explanation — one that has “really resonated”, Sibley says — is that people with ADHD need a degree of activity and accountability in their lives to perform and stay engaged. Sibley thinks there might be a U-shaped curve: too many or too few demands and obligations mean that people with ADHD don’t function at their best — but at a “sweet spot,” they do.

Such studies fan a lively debate about how best to treat ADHD. Clinical guidelines from the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend offering medications — often stimulants such as methylphenidate (commonly sold as Ritalin and Concerta) — as a treatment for children aged five and over. But this applies only after parents are given ADHD education and support, and only if the child’s impairment persists after ‘environmental modifications’ have been implemented, such as reducing distractions at school (see go.nature.com/48fxtsb). NICE recommends that the first-line treatment for children under five should involve parent-training programmes, which typically teach behaviour-management techniques such as setting clear ground rules.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends the use of medications and behaviour therapy, such as parent training and adjustments made in schools, for children aged 6–12.

A meta-analysis based on studies published up to 2020 aimed to address controversy over whether ADHD medications are over- or underused, by pooling data mostly from high-income countries. It found that medication was being taken by 19% of school-age children diagnosed with ADHD — much less than the roughly 70% that the study estimated might benefit from trying such treatment. It also found that almost 1% of children without a formal ADHD diagnosis were receiving medication.

But medication is “a very hot topic”, says Cortese. There has been a tension, he explains, between those who favour treating ADHD with medication and those who advocate alternatives.

A systematic review published in January aimed to address this tension. For the first time, it compared the effectiveness of all types of intervention for ADHD in adults by synthesizing evidence from rigorous randomized trials. This showed that stimulant medications and a drug called atomoxetine were effective at reducing the ‘core’ symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity after 12 weeks. “Only the medications have a level of evidence which support their use to treat these symptoms,” says Cortese, a co-author of that review. “The evidence is quite clear.” The review found weaker evidence that cognitive behavioural therapy, which aims to change unhelpful thoughts and behaviours, improves core symptoms in adults. But plenty of other research suggests that behavioural approaches can be effective at improving other outcomes for adults and children with ADHD.

Researchers acknowledge that ADHD medications can have side effects and come with many unknowns. Some research suggests that taking stimulants is linked to a reduction in the expected height and weight of children14. But one large epidemiological study in Sweden found that ADHD was linked to shorter height even before stimulant medications were introduced to treat it there — suggesting that some other genetic or environmental influence might actually account for all or part of the reduced height. It’s important to discuss the “trade-off between benefits and harms” with patients, says Edoardo Ostinelli, who studies precision medicine in psychiatry at the University of Oxford, UK.

The long-term effects of ADHD medications are harder to study rigorously, so evidence is more scarce. In one study published in August, Cortese and his colleagues examined the records of nearly 150,000 people diagnosed with ADHD in Sweden between 2007 and 2020, of whom more than half had started on drug treatment such methylphenidate. After controlling for confounding factors, the researchers found that taking medication was linked to lower rates of suicidal behaviour, substance misuse, criminal convictions and transport accidents, compared with a group that did not take medication.

Stimulants have been used for decades, and “there’s really a vast literature” that supports their use, Bölte says. “It’s probably the most effective medication we have in the whole of the mental-health sector.”

But clinical specialists who spoke to Nature emphasized that support should involve offering a range of approaches, and that individuals should work with specialists to decide what is right for them.

Wiznitzer says that data do not support claims in the ‘Make America Healthy Again’ (MAHA) report that ADHD treatments are overprescribed or ineffective in the long term. “There’s an increased rate of prescription because we’re identifying the kids better,” he says. The comments in the report about stimulants “do not look at the totality of the evidence that we have about their efficacy,” he adds.

How to select the right approach for an individual is one area that would benefit from a more scientific approach. People with ADHD have widely differing traits and responses to medications, but researchers lack a detailed understanding of why.

Cortese, Ostinelli and their team are developing a digital tool — based on data from randomized trials and the health records of people with ADHD — that will suggest treatments that best match a person’s ADHD symptoms. This, they hope, will improve on the current trial-and-error approach.

Two other big challenges for people with ADHD are access to diagnosis and treatment, and misinformation, says Didier. In one 2022 study, clinicians rated more than half of TikTok videos about ADHD as misleading. “They’re being bombarded with myths about what ADHD is and isn’t,” she says. And statements from Kennedy — such as using questionable data to link Tylenol (paracetamol) use in pregnancy to autism and ADHD — could add to the problem, some researchers say.

Nature asked the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to respond to criticisms of statements from Kennedy and the MAHA Commission. An agency spokesperson said: “HHS is committed to expanding efforts to improve the safe and appropriate use of medications in children.”

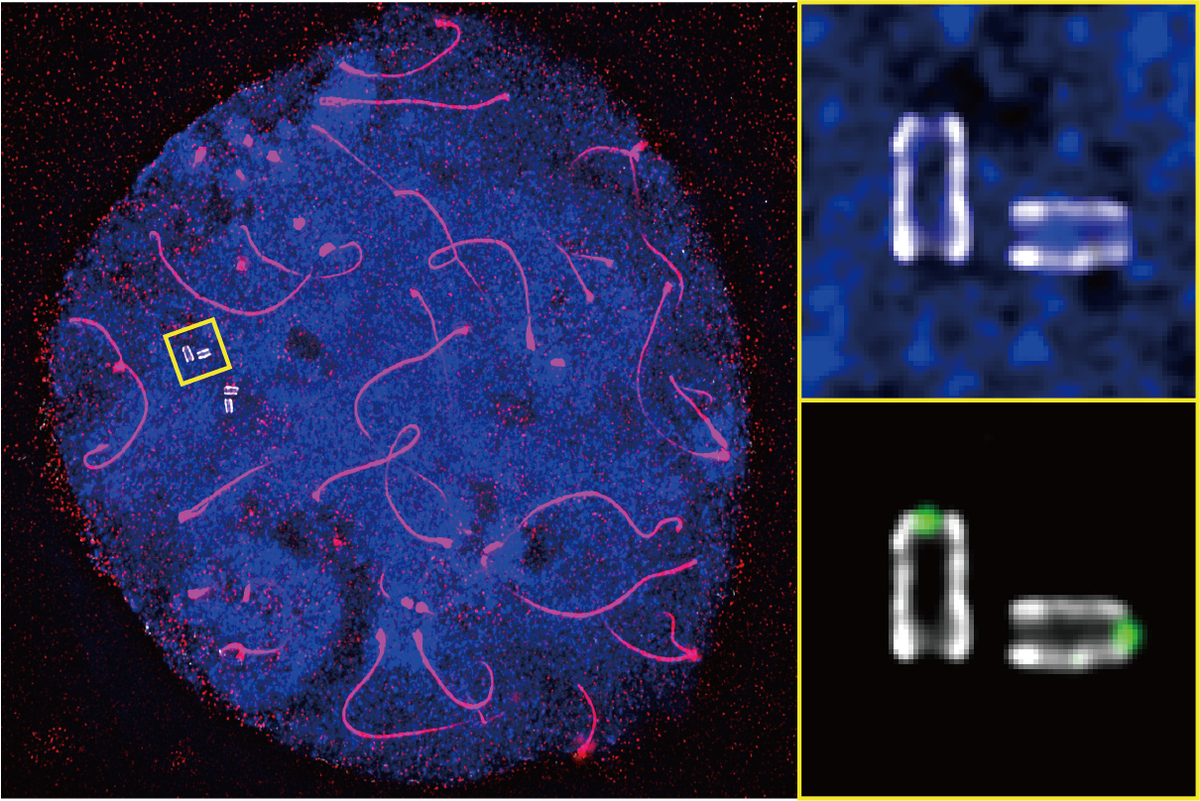

For their part, scientists want to learn more about how brain circuits develop and operate in people with ADHD and, ideally, find biological markers that could be used to improve diagnosis of the condition. And researchers have not been able to test all the ideas generated by people who have experience of living with ADHD, says Sibley.

But a lot of puzzles about ADHD remain unsolved, says Sibley, because the broader medical field tends to view it as less serious than other chronic health conditions, such as depression, that pose a more obvious threat. “That’s the uphill battle,” she says.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on November 26, 2025.