Scientists Pinpoint Gene in Sperm That May Be Key to Male Infertility

Without the gene Poc5, male mice produced no viable sperm, pointing to a possible link to infertility

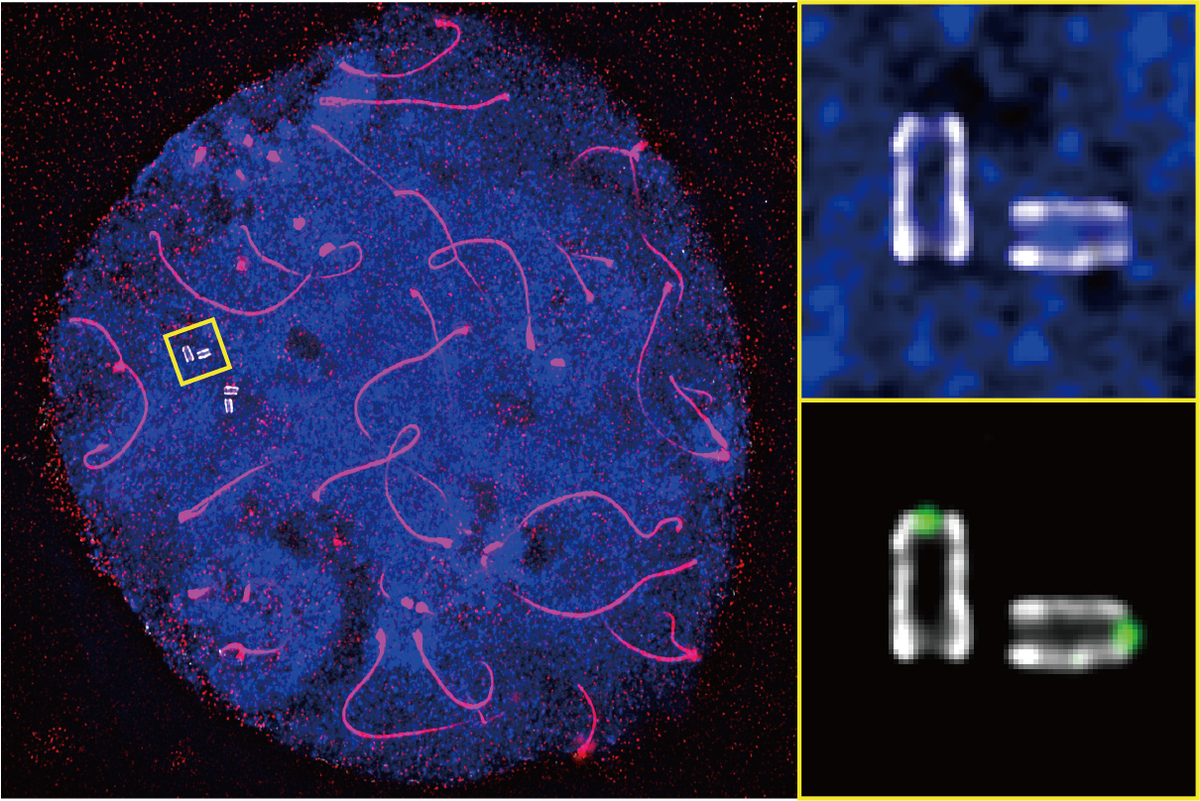

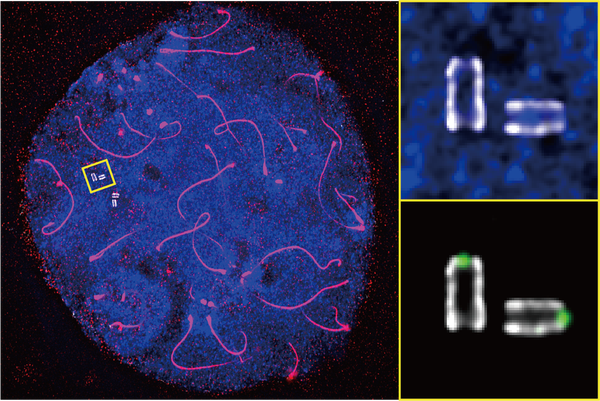

Ultrastructure expansion microscopy of murine male germ cells reveals the fine molecular structures of centrioles (shown in the enlarged image). DNA is stained in blue and the chromosome axis in red.

Scientists have identified a protein that may be key to proper sperm formation. Without it, male mice produced no viable sperm, they found.

A team at the RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research in Japan found that a protein called Poc5 appears critical to the development of sperm’s tail—the vital part that helps them swim toward an egg in order to fertilize it.

“This discovery directly advances our understanding of how the human sperm tail is formed” because mouse sperm share important similarities with human sperm, says study co-author Hiroki Shibuya.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“If our [microscopy] technique is applied to human spermatids, it will become possible to identify exactly which structural abnormality underlies infertility,” Shibuya says. The results were published on Wednesday in Science Advances.

Infertility affects one in six people around the globe, according to the World Health Organization. And an estimated 50 percent of cases of infertility involve male factor issues. Yet despite being so common, the causes of male infertility are poorly understood, and most infertility treatments focus on treating women.

“When a male is infertile, the burden falls on the female,” says cell biologist Tomer Avidor-Reiss of the University of Toledo, who was not involved in the study.

Part of the reason why male infertility has been relatively neglected is that the formation of sperm is complex and hard to study because they are so small: it’s just hard to see their structure in detail. Developing sperm cells rapidly condense their DNA to form a head and then a tail that allows them to move. Any hiccup along the way can cause infertility, Shibuya says. “Identifying the precise cause in each patient is extremely challenging,” he says.

Shibuya and his team decided to focus on the tail. On it sit a pair of tiny cylinders called centrioles. Using a technique called ultrastructure expansion microscopy, the team were able to enlarge the cells to many times their original size, illuminating how the centrioles changed during sperm development for the first time.

The researchers found that, inside one centriole, there is a kind of scaffold that gets stronger over time. They already knew that a protein called Poc5 plays a role in the centrioles’ shape and function. So Shibuya and his team created gene-edited mice that lacked the Poc5 gene, which produces the protein. While the male mice appeared to develop otherwise normally, the tails of their sperm were poorly formed and often fell apart.

Identifying genes is an important step toward treating infertility, says geneticist Susan Dutcher of Washington University in St. Louis, who wasn’t involved in the new study. “When you have these kinds of problems, it is nice to know what causes them,” she says. Although this is not the first time scientists have used expansion microscopy to analyze sperm, the technique is essential for advancing reproductive science, Dutcher says.

More studies are needed to determine whether Poc5 plays the same role in human sperm, Avidor-Reiss says.

Shibuya’s team is already pursuing an effort to repeat the experiment in other animals, including lizards, hamsters, marsupials, marmosets and macaques, although these results have not yet been published. Even so, he says, “there are essentially no technical barriers to applying this method to human sperm.”

Editor’s Note (12/4/25): This article was edited after posting to correct Tomer Avidor-Reiss’s surname.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.