First solar eclipse of 2026 blazes a ‘ring of fire’ above Antarctica

A stunning “ring of fire” eclipse was totally visible to a lucky few in the Southern Hemisphere. Here’s how to see the next one

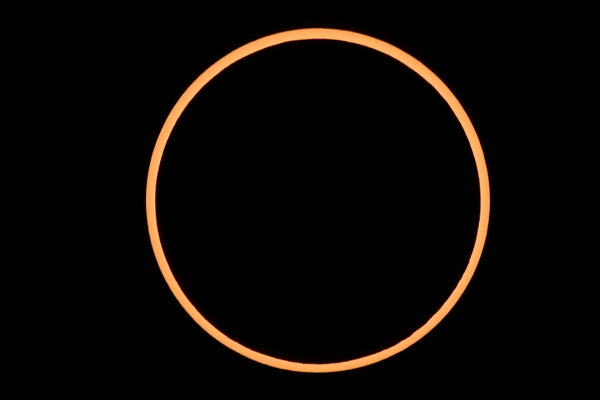

A “ring of fire” effect during an annular eclipse of the sun over Albuquerque, N.M., on October 14, 2023.

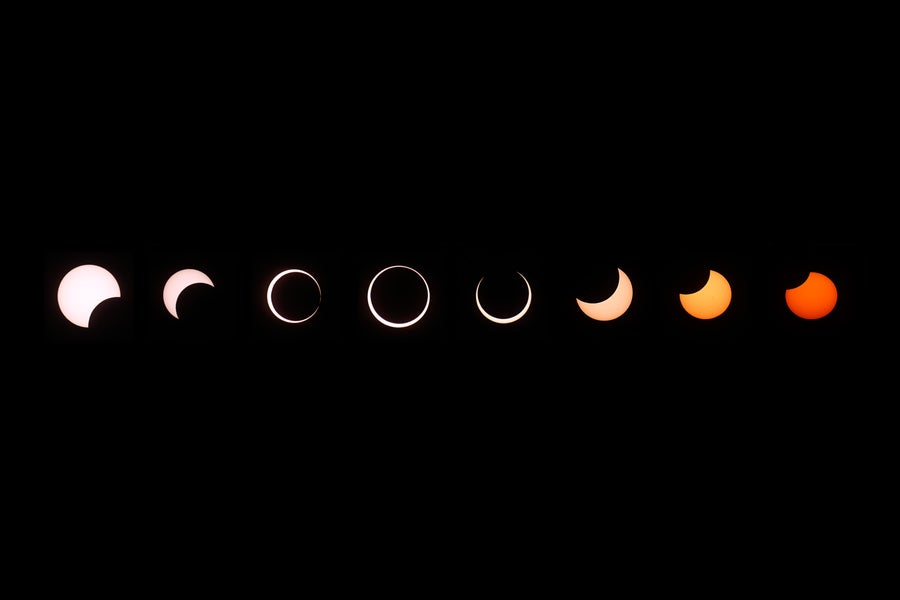

On Tuesday parts of the Southern Hemisphere were graced by a “ring of fire” solar eclipse—a celestial marvel that occurs when the moon is at or near its farthest distance from Earth and passes directly between our planet and the sun. Because the moon’s diameter appears smaller than that of the sun, our star looks to us like a fiery halo of light in the sky, hence the eclipse’s nickname.

The solar eclipse, the first of 2026, reached its maximum at 7:12 A.M. EST. The phenomenon was visible in some parts of Antarctica, Africa and South America.

The event, also called an annular solar eclipse, reportedly lasted about two hours from start to finish as viewed from Concordia Station in Antarctica, and the fiery ring was visible for just more than two minutes. Only sky-gazers in Antarctica would have seen the full ring.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

If you weren’t among the lucky people—or penguins—to have caught the eclipse, do not fret: another one is coming soon.

A total lunar eclipse—in which Earth passes between the sun and the moon, and we see our natural satellite’s color turn to a bloody red—is due to take place on March 2. And a total solar eclipse—when the moon passes in front of the sun and fully obscures the star from our view—will grace the Northern Hemisphere on August 12. The solar eclipse’s path of totality, where people can expect the sun to disappear, will traverse the Arctic, Greenland and Spain. But viewers in parts of North America, northern Europe and Africa will still be able to see a partial eclipse.

A composite of images of an annular solar eclipse on May 20, 2012, in Arizona’s Grand Canyon National Park.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.