Death by Fermented Food

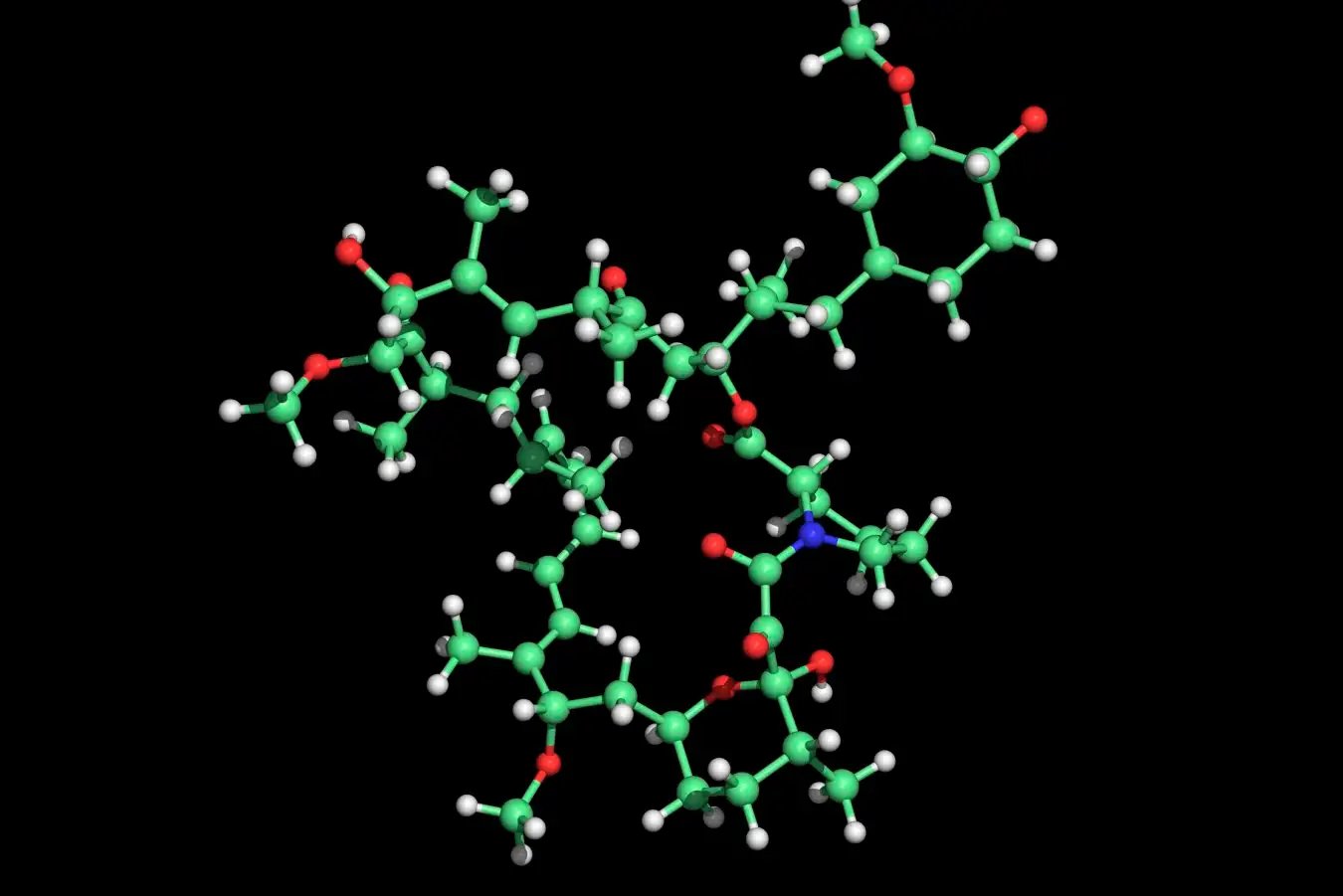

Some fermenting foods can carry the risk of a bacterium that produces an extremely strong toxin called bongkrekic acid

danikancil via Getty Images

I only developed an enthusiasm for fermented foods a few years ago. I used to not even like yoghurt, whereas now I eat it almost every day—and I’m always happy to reach for kimchi, miso and sauerkraut. Many nutrition guides claim that I’m doing something good for my body.

In most cases, this may well be true. But in some fermenting foods, a bacterium thrives that produces an extremely strong toxin called bongkrekic acid. Unnoticed, this accumulates in the food and gives anyone who eats it a dangerous case of food poisoning, as shown by an outbreak of illness that occurred in October 2020 in a town in eastern China.

Twelve people had breakfast together at home. Nine of them were dead within the next two weeks. They all had one thing in common: they had eaten sour soup. The dish contained noodles that the hosts had made from fermented corn (stored too long and too carelessly). It only took a few hours for the poisoning victims to develop the first symptoms. At first they noticed abdominal pain, they felt nauseous and vomited. Some developed diarrhea and all of them quickly became very unwell. The symptoms became so severe that they sought medical help on the same day. However, the doctors were unable to help them. The first patient was dead just 20 hours after the symptoms of poisoning began. Six more followed in the next 48 hours. The last two lasted a few days longer, but they also did not recover from the disease, and in this case all the people who had ingested the toxin died.

Overall, around half of such encounters with bongkrekic acid end fatally. Even the smallest amounts of the substance—one to one and a half milligrams—can cost an adult their life. In the tragedy described, the Chinese authorities found a concentration of 330 milligrams per kilogram in the homemade noodles that the victims had eaten. Assuming a consumption of around 100 grams per person, this is around 20 to 30 times the lethal dose of the poison.

The preparation of the food made no difference. Unlike the bacteria that produce bongkrekic acid, the substance itself does not decompose during cooking. And neither the taste nor the smell of the dish indicates its presence.

While a maize preparation was the downfall here, bongkrekic acid was originally associated primarily with another food. The toxin was even named after it: Tempeh Bongkrek. Tempeh is made from fermented soy. After soaking and cooking the beans, mold spores are added and the mixture is left to ferment for around two days in an airtight container. The resulting mass of plant and fungus can then be seasoned and fried or deep-fried.

In addition to soy, tempeh bongkrek also contains coconut pulp as a further ingredient. And the Burkholderia gladioli bacterium, which can produce bongkrekic acid, prefers to grow in this pulp. More precisely, it is a particular strain of this bacterium that produces a particularly large amount of the toxin, Burkholderia gladioli pathovar cocovenenans, or B. cocovenenans for short. Because the consumption of tempeh bongkrek in Indonesia has resulted in thousands of cases of poisoning, the country’s government felt compelled to ban its production in 1988. But just as Germans would not allow their sauerkraut to be taken away from them, the same can be said of tempeh bongkrek. Even today, people still produce it for private use or for the black market.

B. cocovenenans likes to grow on moist, starch-rich cereals if they begin to ferment—either deliberately or due to unsuitable storage. In addition to fermented maize preparations, these foods can include sweet potato flour and rice noodles, which have been blamed for some outbreaks in China.

While the cases continue to be concentrated in South East Asia, in 2018, the disease also appeared in Africa for the first time. Between January 9 and 12, 234 people in Mozambique fell ill after consuming the drink Pombe, a traditional drink brewed from maize flour. A total of 75 of people died from the poisoning.

And in 2024, there was a case in North America. The victim had prepared a dish of fermented corn flour. When he went to hospital two days later, he complained of nausea, vomiting and exhaustion. At this point, his liver and kidneys were already severely damaged and his blood was acidic. His condition deteriorated steadily over the following days and he died in hospital eight days later. So far, no cases of bongkrekic acid poisoning have been observed in Europe, but it cannot be ruled out that B. cocovenenans will appear there at some point.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

This article originally appeared in Spektrum der Wissenschaft and was reproduced with permission.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.